- Home

- Stormy Daniels

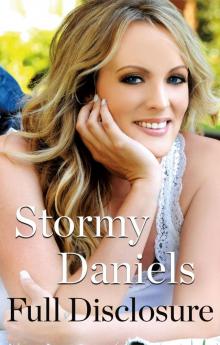

Full Disclosure

Full Disclosure Read online

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my smart, brave, beautiful daughter. You remind me every day what truly matters.

NOTE

From the moment I first met her, I knew Stormy Daniels was different. I’ve had the good fortune to meet a lot of people along the way from different walks of life—janitors, construction workers, hard-working blue-collar workers, middle managers, executives, working moms, homemakers, and CEOs. From people who were broke and down on their luck to billionaires who will never want for anything. But I’ve never met anyone quite like Stormy Daniels.

What makes Stormy Daniels so unique—and so prepared for the important role she has undertaken—is that she always owns who she is. She is entirely confident in her own skin—every day. She doesn’t try to pretend to be something she isn’t. Not even when sometimes I wish she would (see her Twitter account). In a day and age where image is everything and everyone is vying for that perfect Instagram pic or the ideal tweet, Stormy is … herself.

That is very refreshing. And it is something to be cherished.

Her journey so far has been an amazing one. And we don’t know yet where it ends. My hope for this book is that it will let you learn who Stormy Daniels really is. I am confident that when you do, you will agree that we are all very lucky to have her.

—Michael Avenatti, Esq.

PROLOGUE

My phone buzzed again and again with friends texting me the same message: “Happy Stormy Daniels Day!” It was two o’clock, and I had two hours before the city of West Hollywood was set to give me the key to the city at an outdoor ceremony on Santa Monica Boulevard. Mayor John Duran had proclaimed May 23 to be Stormy Daniels Day, and yes, it seemed just as surreal to me as it did to everyone else.

I texted each friend back, sipping a Red Bull. My gay dads, Keith and JD, know to keep the house stocked with energy drinks when I come stay with them in L.A. And snacks. If you and I are going to be friends, we need an understanding that there must always be snacks involved. My two bodyguards, Brandon and Travis, pulled up to the house in an SUV. They have been at my side since the beginning of April, when the death threats against me and my family started ratcheting up, but I have never seen them nervous until that moment as they walked up to the house carrying a bag. I had given them a very important mission: go to Marciano to pick out a dress for me to wear to the ceremony. “I’m a small right now,” I had told them, “but keep in mind I have big boobs.”

To hedge their bets Brandon and Travis bought two dresses, in peach and black, and presented them to me for approval. I narrowed my eyes, because hazing the people I love is a favorite pastime, before saying quietly, “Guys, you did great! Bodyguards and stylists?” I went with the black one, a Capella cutout bandage dress which fit perfectly, and kept Thunder and Lightning—my nickname for my breasts—in check.

I think I put off buying a dress because I was so nervous about giving a speech. Because I am an adult film actress, director, and dancer, when I meet people they usually have some nagging question about what gives me the nerve to think I can do something. How do I do porn or take my clothes off onstage in clubs? Or take on the president of the United States? No, the thing that amazes me most about this past year is that I can speak in front of people. Because when I was a student at Scotlandville Magnet High School in my hometown of Baton Rouge, sure, I got straight As, but I always took a zero rather than talk in front of the class. My fear was so crippling, my voice so shaky, that I could not get out of my seat. The first time this happened was in ninth grade—an oral book report on Little Women. Of course, I read it—I read everything I could back then. And Jo March was the perfect character for me to talk about because, just like me, she wanted to be a writer. More than that, I identified with Jo’s frustration with what the world was ready to allow a girl to do. And no, I did not think she should have married old Professor Bhaer. (Sorry if that is a spoiler, but if you narrowed your next read down to this one or Little Women, you need to examine your life choices.)

But I couldn’t get my voice to come out. I took a straight-up F, and did so every time an assignment called for public speaking. I didn’t want people looking at me. Judging me. Which is exactly what has happened ever since March, when I gave 60 Minutes a free interview that was worth millions. It was important to me that I go to a reputable, impartial news source when I first set the record straight about Donald Trump’s personal attorney repeatedly trying to get me to lie about a sexual encounter I had with the president in 2006. The interview covered what happened in a hotel room, and later, when my life was threatened in a parking lot. But it wasn’t the full story—it didn’t cover the “why” of my decisions and the real, personal costs to me. I was starring in films I wrote and directed in L.A., then going home to my suburban life with my husband and seven-year-old daughter in Texas. It’s the life I dreamed of and worked hard to have, and I have to keep reminding myself that that life is over. For all I’ve lost, I deserve the chance to defend myself and state all the facts. That’s why I chose to share what you are about to read.

I’m also doing this for all the people who have come to see me dance in my shows, waiting in longer and longer lines to take a photo with me and share a moment. I have been dancing in clubs since I was seventeen. As my fan base grew over two decades of work in film and feature dancing, my demographic was usually middle-aged white men. Forty-five- to sixty-five-year-old white dudes—Republicans, basically. I lost a lot of them, and that’s their choice. This is, after all, America.

They were replaced and outnumbered by people of color, gay men, and lots and lots of white women in their forties. These are people who have never come to strip clubs before, and there’s a learning curve to a strip club. My old crowd was well versed in the etiquette, thank you. If they specifically came to see me, it meant they were into adult entertainment, so they had likely been to a convention or at least seen another porn star at a strip club. They know how to act. They don’t take pictures during the show, and they definitely don’t grab me to tell me they love me. Because I’m in heels, and if a guy pulls me, I will fall. And a bouncer will throw him out, Roadhouse style.

If you’re familiar with the term “New Money,” you will understand the concept of New Strip Club Patron. And now my shows are full of them. The gay men seem to fall into two categories: the good-timers and the witnesses to history, and I love them both. I can’t tell you how many times men from the former group have told me, “This is the first time we ever paid to get into a strip club—that has a vagina.” A lot of them come with props for the meet-and-greet photos, like bags of Cheetos or a Make America Gay Again hat. The latter group of gay men is more emotional, and after the show they talk to me about feeling bullied by an administration that makes their marriages and freedoms seem less safe. Their fear is real, and when they confide in me, it comes from an authentic place. It was shared by my gay dads, the family I chose in my twenties when I gave up on my biological parents. Keith and JD were two of the only people who knew that I had a secret about Trump pre-election, and there was a time after the 2016 election when their concerns about their upcoming marriage turned into resentment of me for not coming forward and upending my life to save theirs.

I realized the women were coming out to see me when I started getting hurt Facebook messages from strangers some mornings after my shows. “We came to support you but they didn’t let us in!” Packs of single women were coming to the clubs in groups of four or five,

only to be turned away by bouncers. Normally, a straight woman can only come in the club if she is escorted by a man, because it’s assumed that if she’s solo she is looking for a husband or a sale. Now, I make sure the club owner knows they have to let women in.

The women I see on the road have a lot of anger. Not at me, which I initially expected. I was worried I wouldn’t be safe anymore in clubs. No, they’re angry at Trump, who seems to be a standin for every man who’s ever bullied them. Nashville, Shreveport, Baltimore … “You have to get him,” they say. “Get that orange turd.” Many of these women are quieter as they wait in line to talk to me, then grip my arm to tell me about someone they didn’t speak up for. A friend who killed herself after being raped. Or their own stories, feeling voiceless and unprotected. I stand there, a girl in a cute dress who just stripped onstage a few minutes before. These women transfer all the energy to me and leave feeling unburdened, but now it’s mine to carry.

They leave me with “You’re going to save the world.” In April, a woman at a meet-and-greet upgraded my job to saving the universe. No pressure. It’s these women who gut me, never the Twitter troll who calls me a slut or the guy in a crowd yelling “whore.” I sometimes think my job in porn prepared me for all this, because you can call me any name in the book and I’ve heard it from some other judgy loser. But nothing in my life prepared me for the confidences and hopes of people who come to see me. Even though it’s all positive energy, it’s still all pointing at me. The best way I can describe it is going to the beach and being in the sun all day. It’s great, but you feel sick when you get back to your room. In my case, it’s absorbing it all until it hits some limit I didn’t see coming, and I am suddenly on the floor of my hotel room, sobbing when no one can see me. I let myself feel it once, and then I get back up. I call it wringing out the sponge.

Besides, it was Stormy Daniels Day, and the hero had to show up and speak. Before I left, I FaceTimed with my daughter, who was home in Texas with the tutor we had to hire because it’s impossible to send her to school and shield her from what everyone is saying about her mother. She was at a zoo with her tutor, and for ten minutes, I stopped everything to hang on every brilliant word of a seven-year-old’s telling of her day’s adventure.

“I can’t wait to see you not digitally,” she said.

“I’ll see you Friday, baby,” I said. “How many sleeps is that?”

“Two.”

To avoid paparazzi taking pictures of our family, we’ve had to arrange meet-ups in other cities. People learned that if there was even a two-day gap in my schedule, I would be home with my girl in Texas. They camped out at the house and the stable where we ride. This time we’d be going to Miami, where at least she could swim with dolphins.

“Mommy loves you,” I said.

And then my little traveling circus was off to the ceremony. When we got to Santa Monica Boulevard, there was a friends-and-family area inside Chi Chi LaRue’s store. Keith and JD were inside, greeting everyone, in total hosting mode for their daughter’s day. Mayor John Duran and Mayor Pro Tem John D’Amico arrived, followed by my lawyer, Michael Avenatti. As always, I smiled at how many people wanted a picture with him and how many people made excuses to touch his arm. An assistant to the mayor asked Michael if he’d like to speak, but you know how shy he is. Kidding—of course he said yes. As always, he offered to write my speech for me, and as always, I said no. Partly because I know it scares him, but mostly to make it mine.

A throng of people had shown up, and the floor-to-ceiling windows of the store gave it the feel of a fishbowl, with photographers and fans pressed against the roped-off speaking area outside. Brandon and Travis paced, already scoping for trouble in the crowd.

“You ready?” Michael asked me.

I nodded. The mayor, mayor pro tem, my gay dads, Michael, and my dragon bodyguards all crowded onto the tiny stage. “There’s one thing I can promise about Stormy Daniels,” Michael told the crowd. “And that is: She’s not packing up; she’s not going home. She will be in for the long fight, each and every day until it is concluded.”

John D’Amico handed me the key to the city, and the girl who took a zero rather than be judged just started talking. “So, I’m not really sure what the key opens,” I said. “I’m hoping it’s the wine cellar. But in all seriousness, the city of West Hollywood is a truly special place, very close to my heart.”

A man in the crowd started yelling, “How big is Trump?” Keep going, Stormy, I thought.

“As a woman with two wonderful gay dads, Keith and JD, I feel especially at home here. The community of West Hollywood was founded more than three decades ago on the principle that everyone should be treated with dignity and fairness and decency.”

“How small is Trump?”

“And this community has a history of standing up to bullies and speaking truth to power. I’m so very, very lucky to be a part of it.”

Back inside, I read the mayor’s proclamation and I was again struck by the absurdity of my life. I should be living in a trailer back in Louisiana, with six kids and no teeth. I grew up in a house that I should never have escaped, with adults never coming to my aid. I started stripping in high school and still graduated with honors as editor of the school paper. I won the respect of a male-dominated industry as a screenwriter and director. And despite everything I did to stay out of it, I ended up in the middle of one of the biggest political scandals in American history.

I know that the deck has always been stacked against me, and there is absolutely no reason for me to have made it to where I am, right here talking to you. Except that maybe the universe loves an underdog as much as I do. I own my story and the choices I made. They may not be the ones you would have made, but I stand by them.

Here’s my story. It has the added benefit of being true.

ONE

We watched as the tornado tore through the field of sunflowers.

It was a little skinny one, miles away from where my mom and I sat on the front steps of our building. North Dakota was so big and flat that you could sit in the bright sunshine and watch a storm blow through in the distance like a movie. This was late July, the summer we lived in a Bismarck apartment complex that looked to two-year-old me as if it had been pulled from Sesame Street. Our building was across from a sunflower farm, black and gold flowers facing east as far as you could see.

“Look at the twister,” my mom kept saying. “Look at the twister.”

I wasn’t scared. I was never that kind of kid. I was the girl who walked home from the Little People Academy preschool when I was two. Just slipped out during naptime. “I don’t nap,” I told my mother when she answered the door. She sighed. I had confounded her since birth, when the boy she had planned and decorated a nursery for turned out to be a girl. She was inconsolable for a week. I was supposed to be called Stephan Andrew after a late relative, but she and I were stuck with Stephanie Ann. If we should ever meet, call me Stormy.

That summer of the tornado, my mom bought me black roller skates with red laces and red wheels. I just loved the look of them, but she was determined to teach me how to skate. She’d put me down on the concrete and hold her arms out. “Come here,” she’d say. Sheila Gregory was beautiful then, a twenty-seven-year-old Julianne Moore look-alike with freckles and blue eyes. She wore her strawberry-blond hair long and straight, parted in the middle, a seventies look she successfully brought with her into 1981. She was short and thin, and people would say, “Aren’t you a tiny thing?”

She seemed even smaller next to my dad. Bill Gregory is six foot four, with chiseled features and olive skin owed to Cherokee blood somewhere in the line. I am a perfect combination of Sheila and Bill, a mix that could have gone horribly wrong. I had tight, super curly blond hair, and I am smart like my dad. We traveled for his work as an architectural engineer, going to new water treatment plants to map out where the electricity should go. My mom was not what you’d call a big thinker. She’d never had a job in her life,

and I can’t recall her ever even picking up a book.

What my mom did care about was my father. They had a very passionate relationship, and she had a jealous redhead temper. She liked to throw things, though never at me. Just warning shots at him. She had had her pick of men and went on some dates with Kurt Russell when she was seventeen. She met him at the Louisiana State Capitol while she was with my grandmother, who had jury duty. Kurt was there shooting a movie, The Deadly Tower. He took one look at my mother and he was a smitten kitten. He asked her out and my grandparents let her go, but supervised. Even my grandmother would talk about the night Kurt Russell picked my mom up in a limo and they went to a fancy dinner. Then he didn’t get anywhere because she was underage. They held hands, so that was the end of that.

Bismarck was just a quick stop for us. We kept a house in Baton Rouge, where I was born, and my father’s parents lived next door so they could keep an eye on the place. But we were rarely there. Our Suburban was always packed up, and my dad had a matching boat, which went everywhere with us, no matter how landlocked the new place might be. Any chance he had to take it out for waterskiing, he took it. Otherwise, it was just a trailer. We’d load all our stuff in it, put the cover on, and drive to the next place.

I have a photographic memory, so I can put myself right back in every place we lived. There was Kissimmee, Florida, and the winter in Kalamazoo, which my mom hated. All she did was complain and smoke in the house because Michigan was too cold to go outside. After Bismarck we moved to Idaho Falls. We rented a house on Amy Lane, a tiny street dotted with spruces that looked like Christmas trees. We had a big beautiful backyard with a long concrete sidewalk leading to a barn that still had horse stalls. Somebody who lived there had kept horses, and I would sit in the cool of the barn, trying to summon the ghosts of these horses.

Mom made a friend, Nicky Fontenot, who I called Miss Nicky. She owned a horse named Prissy Puddin’ and she barrel raced. One day I was at the stable, and Miss Nicky was cooling out the horse after racing. Prissy was sweaty and tired, and someone put me, all of two, up on the horse to sit in front of Miss Nicky. I can remember the smell of the saddle and the horse sweat, her bay coat and black mane. It was magic, and I don’t know a time since that I haven’t wanted to ride.

Full Disclosure

Full Disclosure